Tell me what you goin’ do to me

Confrontation ain’t nothin’ new to me

You could bring a bullet, bring a sword, bring a morgue

But you can’t bring the truth to me

~ Kendrick Lamar

I believe the truth leads to freedom. Silencing the truth leads to oppression. The story of my experiences in the nonprofit sector has been a reality of clashes among those concepts. Let me first expose the historical fabric lying beneath the meaning of freedom for Black people in Canada.

This year on August 1, my family will again commemorate Emancipation Day. It is a tradition of descendants of the Underground Railroad. It is a freedom celebration. On August 1,1834, the Slavery Abolition Act was enacted. It ended slavery throughout the British Empire including British North America. Slavery became illegal in every province. Slave owners across Canada had to free their slaves.

Photo credit: OurDigitalWorld https://images.app.goo.gl/GtWepGTbbbAHvEqw5

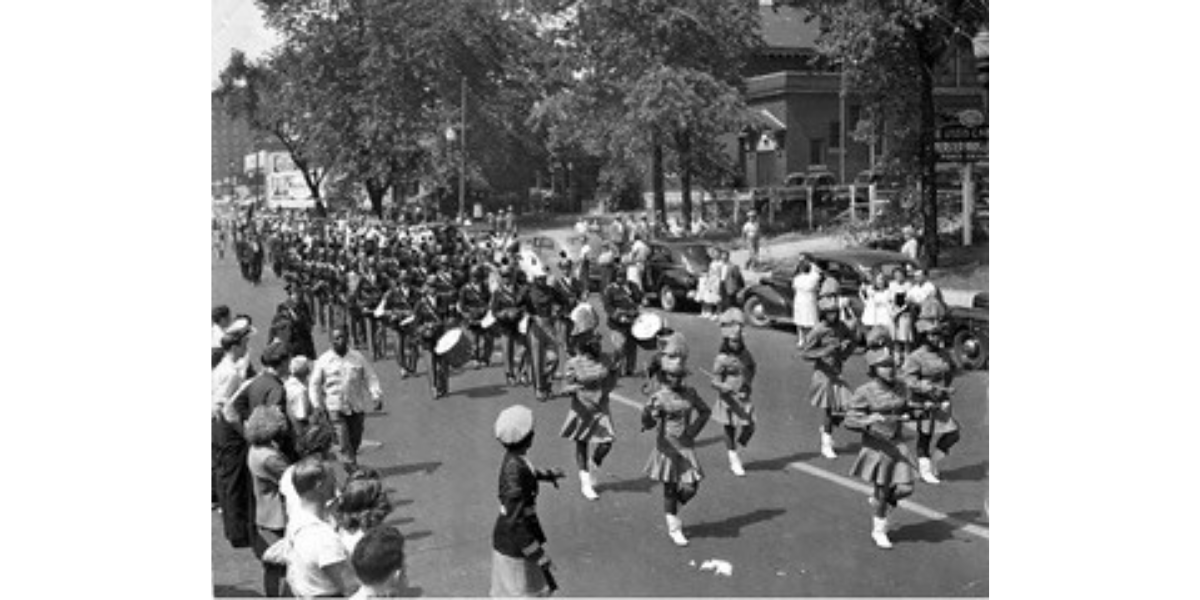

Emancipation celebrations on August 1 have been a custom across Canada. None more so than in my hometown of Windsor, Ontario, where massive events took place in the city centre. In the early period, my paternal grandmother served as the bookkeeper and treasurer to Walter Perry the iconic founder of the local celebration that became, “The Greatest Freedom Show on Earth”. My mother was a young majorette in the bi-national parade that spilled into Jackson Park. People came from all over, Black and white alike. My paternal great grandmother took a key role in inviting such famous guests as Eleanor Roosevelt, Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Mary McLeod Bethune.

My my great-grandmother, Genevieve Allen, is standing on the right of Eleanor Roosevelt.

My mother, Karla Taylor, is the third majorette from the left. Photo credit: The Windsor Star From The Vault, Volume II: 1950 to 1980.

The Emancipation Proclamation is my family’s freedom story. The truth of our story survives because of our oral narrative tradition. As I prepare, in a few days, to celebrate 186 years of freedom for my people in Canada, I ponder. While the physical bondage of slavery is no longer our reality, Black people continue to be modern prisoners in many ways. We are too often silenced from telling our truth. We are too often oppressed by the silence of those who refuse to bear witness even to the truth they actually see. Today, I am leaning into Black people’s oral legacy of truth-telling and confronting the injustice we see.

Black people across the Atlantic are bastions of oral history. Through colonization and structural racism, these practices have been threatened by erasure and, even worse, presented as inferior to Western accounts of our own history.[1]

Griots are the storytellers, the historians of Ancient Africa. They pass on history, stories and shared values through narratives and songs. Griots were important to West African society because they were the keepers of the collective memory. They remembered. And they shared truth.

Modern day griots still have a truth to share. I consider myself one of them. The history books are clear. The stories of Blacks in Canada were excluded. Historians wanted to tell a different “Canadian” story. But erasure does not make not real or not true that which has been erased. In fact, many erased stories form the foundation on which our country is built and prospers today. Indigenous people have joined voices with us on the pain of erasure in Canada.

To be sure racism has left scars on my personal life. But racism has also left deep scars in my professional life. It is my work in the charitable sector that has left me most psychologically and emotionally devastated. Black women like me are fighting for the right to act, to speak and to think authentically. This is a freedom fight. The most powerful weapon in our arsenal is the truth. There is a particular truth that we have been trying to share. Until recently, that truth has been wholly rejected.

Few principles influence success as fundamentally as truth. Truthfulness is the foundation upon which human relationships are built. Truth is the antecedent to trust and trust is the antecedent to cooperation. Without truth, sustainable success is impossible in human dealings.[2]

Prior to the murder of George Floyd and the resulting global protests against anti-Black racism, the pre-George Floyd era, I volunteered on a committee focused on creating greater equity and diversity in the nonprofit sector, specifically for fundraisers.

Notably, there were more Black people than white people on the committee. We laser focused on the true and most obvious issue facing fundraisers of colour, racism. To be clear, this was consistent with the approved strategic direction of the governing organization. And so, we naturally began with education.

We began with a plan to begin to educate and coach the leaders of the organization. The aim was to decolonize their thinking to make way for a better understanding of their perpetuation of anti-Black racism. We ran into a serious road block – whiteness.

The education plan was my responsibility to draft. Coincidentally, I was able to make this practical task part of a final project I was completing for a course at University of British Columbia, Engaging Diversity and Inclusion in Organizations. Importantly, the project required the plan to be academically reviewed by my professor. The plan was applauded by my professor as necessary and radical. In her final email to me she warned me by sharing her favourite Slovenian proverb: “Always tell the truth and leave immediately afterwards”. The education plan did tell the truth. It provided real solutions. But to cut and run, that was not a part of my plan. The impact of anti-Black racism on Black people does not take a break. Our struggle is not optional.

The education plan was enthusiastically received by the Black committee members which, again, were the majority of the committee. Democracy dictates a majority would be sufficient to advance the plan. But that is not what happened.

During a meeting following the committee’s second review of the education plan, all the classic resistance tactics were employed by a small number of white committee members. One woman openly challenged the need to focus on anti-Black racism. She, of course, was completely ignoring the organization’s approved focus on people of colour. Of which, Black fundraisers represent a significant portion. Still other white members used silence to signal doubt.

The classic result – tacit support for the woman who wielded her own “truth” on the Black members. The ultimate result, an open challenge to the truth of our voices and the critical need to address anti-Black racism in our organization and profession. What is more, the vocal member insulted us by announcing that our committee was not reflective of the “community.” The clear message, the committee was too “Black.”

Regrettably, in the end the education plan did not move beyond the failed attempt on the committee. So, no education was provided to the organization.

The organization refused to acknowledge the truth and urgency of confronting anti-Black racism. The shameful result, all the committee members of colour resigned.

It is now a post death of George Floyd era. Today, this same organization, mere months after the failed plan, has put out a clarion call. It has positioned anti-black racism as an urgent priority they now want to “resist and fight.” They want training. They want to offer training. They want to be seen at the forefront of the fight against the very form of racism they rejected months earlier.

This attempt to repackage our truths and market them back to us is unacceptable. We cannot forget who rejected our wisdom and truth.

The charitable sector is not yet emancipated. The most commonly used subjugation tool is white silence. For Black fundraisers silence means, silence to keep your job. Silence to protect your reputation. Silence to survive. There are too many people working in silence due to legitimate fears of losing their livelihoods, being rejected and being cut off from their life’s work and ultimately being rejected.

In their Dismantling Racism workbook, Kenneth Jones and Tema Okum identified other characteristics of white supremacy culture, including perfectionism, sense of urgency, defensiveness, quantity over quality, worship of the written word, paternalism, either/or thinking, fear of open conflict, individualism, worship of unlimited growth, objectivity and avoidance of discomfort. They note that these “are used as norms and standards without being pro-actively named or chosen…Organizations which unconsciously use these characteristics as their norms and standards make it difficult, if not impossible, to open the door to other cultural norms and standards. As a result, many of our organizations, while saying we want to be multicultural, only allow other people and cultures to come in if they adapt or conform to already existing cultural norms.” [3]

Photo credit: Newspapers.com https://images.app.goo.gl/zKqPFJAUSLnULoJGA

As I watch the evolution of things, I’m grateful for the insurgence of people ready to be honest and join the truth-tellers. I’m grateful they are prepared to look at how the truth points at them and the role they play in the oppression of Black people. When I think about the Black members’ flight from the committee, I again ponder. I relive the battle waged against us because we dared to challenge anti-Black racism. But I believe that battle might have been different today.

Lately, I have felt short bursts of joy in this viral moment. I contemplate, is this moment filled with the potential to rain down liberty and freedom on all of us? But then I wonder, is freedom really the goal? Do nonprofits want to be emancipated?

Many organizations appear thirsty for the waters of justice. Statements of beliefs, statements of support, training sessions, workshops and panels abound. But justice simply doesn’t come that easily. Legitimate justice is pricey. It requires the truth.

For people with power, power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.

Those who perpetrate revisionist history or the violence of exclusion, whether through silence or superiority, have a responsibility to reconcile their behaviour by apologizing for rejecting our truth, our stories and experiences. They must trust our truth. That it is real. That it is authentic. That is when we will be able to build real and true relationships.

Our beliefs shape our values. Our values mold our thoughts. Our thoughts inspire our actions. As such, our lives are merely a reflection of the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves and the world around us…it’s time we have the uncomfortable conversations that will bring us closer to truth, and ultimately bring us closer to each other.[4]

What if we all became truth-tellers? Emancipation might just be possible for the charitable sector. And maybe in the future on August 1st, I will be able to celebrate a more true freedom.

Freedom! Freedom!I can’t move

Freedom, cut me loose

Freedom, freedom, where are you?

Cause I need freedom too

~ Beyonce

[1]Korede Kaneto Akinsete (July 6, 2020) The Importance of Journaling Black Life During Extraordinary Times https://blavity.com/the-importance-of-journaling-black-life-during-extraordinary-times?category1=opinion

[2]Kenneth J. Sanney, Lawrence J. Trautman, Eric D. Yordy, Tammy Cowart, Destynie Sewell (August 2, 2019) The Importance of Truth Telling and Trust https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3430854

[3] VILLANUEVA, EDGAR. Decolonizing Wealth. Oakland, Berrett-Koehler Publishing Inc., 2018

[4] Julian Mitchell (June 16, 2020) It’s Time We Have The Uncomfortable Conversations About Race In America https://blavity.com/its-time-we-have-uncomfortable-conversations-about-race-in-america?category1=opinion

©2020 by Nneka Allen

Nneka Allen is a Black woman, a descendant of the Underground Railroad, an Ojibwa of Anderson Nation, a Mother and a sixth generation Canadian. She is also the principal and founder of The Empathy Agency. They help organizations deliver more fairly on their mission and vision by coaching leaders and their teams to explore the impact identity has on organizational culture and equity goals. Connect with her on LinkedIn today.